- Home

- Lindsey Rogers Cook

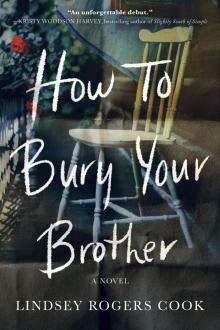

How to Bury Your Brother

How to Bury Your Brother Read online

Thank you for downloading this Sourcebooks eBook!

You are just one click away from…

• Being the first to hear about author happenings

• VIP deals and steals

• Exclusive giveaways

• Free bonus content

• Early access to interactive activities

• Sneak peeks at our newest titles

Happy reading!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Books. Change. Lives.

Copyright © 2020 by Lindsey Rogers Cook

Cover and internal design © 2020 by Sourcebooks

Cover design by Sarah Brody

Cover images © Magdalena Russocka/Trevillion Images, Nenov/Getty Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cook, Lindsey Rogers, author.

Title: How to bury your brother / Lindsey Rogers Cook.

Description: Naperville, IL : Sourcebooks Landmark, [2020]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019038808 | (paperback)

Classification: LCC PS3603.O5725 H69 2020 | DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038808

Contents

Front Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Summer 2007: The Funeral

Chapter One

Winter 2016: 8½ years after the funeral

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Reading Group Guide

A Conversation with the Author

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Back Cover

For my first editor and grandmother,

Dr. Jennie Springer

“I might well say now, indeed, that the latter end of Job was better than the beginning.”

—Daniel Defoe, The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

Prologue

Tuesday really would be the perfect day to die.

I tick through the other days as warmth spreads toward my knees and elbows, out to my fingers and toes like sunlight dancing on the river where I played as a child. It’s the feeling I used to get listening to “Here Comes the Sun.”

Saturday and Sunday, I never considered—why ruin anyone’s weekend? Mondays are bad enough already. On Thursdays, my mother plays bridge, always has, a respite she’ll need, especially this week, so that’s out. Wednesdays—blah—something about the middle of the week, and that’s when the band practices.

My life’s most significant events seem, by default, to occur on Tuesdays. My own birth. My sister’s. Several other happenings, less positive.

The record scratches and silences its melody. Bad timing—a problem I’m doomed to repeat in death as I have since birth, when I knocked on the world’s door during an epic hailstorm that flooded Atlanta, only to draw out the labor, as my mother always liked to remind me, more than twenty-four hours. Maybe I was waiting for the Tuesday. Today, too, the Tuesdayness made me linger, gave this cosmic game of chicken more weight, and I stared too long at the pill bottle.

When I woke up from “the game” these past few times, I wasn’t sure if I’d won or lost, but now God has handed me this answer, this sign. I reach into my shirt pocket, retrieve another pill, and swallow it with what is now gin-flavored, half-melted ice.

I flick my eyes to the record player spinning silently, and it makes me want to cry, just thinking of how, even with YouTube and the internet where anyone can make a record like this one, we still haven’t found another Queen or Nirvana or David Bowie.

My hand grips the glass where it rests on the chair’s arm. The condensation will leave a stain on the leather. Sorry, Lila. I smile, in case this Tuesday really is as significant as it feels. I don’t need another thing to apologize for. If today she finds this worn-down body, I want her to see me smiling, without a tear streak on my face.

Pulsing starts in my chest, edging out the warmth. The tempo enters slowly, like “Hotel California,” then progresses to “Beat It.” When the banging in my chest hits Metallica range, I know. This is it.

A wave of anxiety rises in my throat—or is that something else? Is this what winning feels like? I swallow it down, along with the fear.

I look back to where I know the letters are and sing Nirvana’s “All Apologies” in my head, the song that would be playing were it not for my shitty timing. The shitty timing that will no longer scar anyone I love. Not anymore.

I picture my letters, floating into the universe, down the streets I’ve walked so many times, into the nooks and crannies of my childhood. I picture the black ink of my words finding them, all the people I’ve let down, all the apologies I need to make, all the wrongs I need to make right.

But most of all, her.

Alice.

My life doesn’t qualify me for a last wish or request, I know. But if it did, I would ask that those letters surround her like a shield, that she’d feel that protection, like I can feel her presence now.

She’s calling me.

She says it’s okay to go. She doesn’t blame me for leaving. Not this time.

So I close my eyes,

and let go.

Summer 2007

The Funeral

Chapter One

Alice studied her brother’s mourners through the window of the church. The large Gothic structure in the middle of Atlanta cast a shadow over them as they shuffled in their

shined shoes, their black kitten heels framing hosiery that disappeared under tasteful black dresses despite the thick summer heat. Tears pooled at the corners of Alice’s eyes while she watched them chatting with one another on the way to the door, as if they were heading into any other church service, rather than a funeral. None of them cared about her brother. Alice doubted they remembered his name. She blinked rapidly to stop tears from falling.

“Alice,” her mother said. “Put it—”

“In a box in your mind,” she finished.

Her mother nodded, pleased.

“Maura, give her a break,” her father said. “I mean, look at her.”

Alice removed her hand from her pregnant belly and accepted his offer of a handkerchief. She wiped her eyes.

“Now is not the time,” her mother said.

She was right. Alice had allowed herself seventy-two hours to mourn her brother, and those hours were up—she glanced at the blue plastic sports watch her mother had asked her not to wear—two hours ago, conveniently timed to end before the funeral, so she could smile at all her mother’s friends. The ones who hadn’t considered the existence of Maura’s runaway son in decades, who were only here to build up a type of social capital, so they could ensure that the same people would brave the downtown chaos when the ghost of death came for them. It was time to get the funeral over with, to say a final goodbye to the person she’d already spent a lifetime saying goodbye to, and then to move on with her life.

“Showtime!” said Jamie, in a faded gray suit and a cheerful purple tie. Her father’s best friend helped Alice up from the window ledge, and she trudged over to where her mother had positioned herself in a type of receiving line by the door, ready for the sea of supposed mourners.

* * *

Before the first stranger entered the church, Alice rubbed her neck and prepared to straighten up into a posture her mother had forced her to perfect during her teenage years with a knuckle to her vertebrae. Lack of sleep wasn’t helping her meet her mother’s standards for looking presentable. Instead of sleeping, Alice had spent the previous nights cycling through familiar dreams of her brother, which all ended the same: “Please,” she would beg. “Don’t go.” But he always did, slinging his guitar and duffel over his shoulder, the way he had the last time she saw him, and taking her childhood with him.

Closest to the door, Maura hugged the first couple. “Most people don’t know how pretty a hand-cut diamond can look,” she said, still holding the woman’s wrist. “Have you lost weight?” she said to a man with a salt-and-pepper mustache.

Alice’s father, Richard, offered each man, woman, and child a handshake. To his only living cousin, he volunteered “Harold” and a nod before his eyes returned to his shoes.

Jamie lingered behind, waiting for Maura to invite him into the family’s line. Though he was close enough to the family that everyone at the church had forgotten he wasn’t actually Richard’s younger brother, Maura turned her cheek in refusal to his silent question. Instead, he trapped men in a conversation about his latest hobby—online gaming—as they finished talking to Alice. “These kids, you would not believe,” he said, lifting his arms. He curled his fingers and darted his thumbs up and down in demonstration.

Her brother would have despised this scene. If he were here, he would have led her to the narrow staircase and up to the sanctuary’s balcony, like he always did as a child on Sundays. They would invent fake nonsense conversations as they watched the people in their fancy outfits, Alice laughing so loudly their mother would give a stern look from below. Or they would talk, the scratchy carpet itching the back of Alice’s legs, exposed in one of the ruffled dresses her mother always made her wear to Sunday school.

“What do you think heaven’s like?” he had asked her once, as they tried to count the ceiling’s intricate tiled diamonds. He couldn’t have been older than twelve.

“Angels and singing,” she said with a child’s confidence. “And lots of animals. With wings.”

“In heaven, I want to live in a high, high building where I can play guitar on the roof and look out at earth. And you can live next door in a tree house over the forest. And we’ll see each other all the time.”

She hoped he was there now, but the larger, practical part of her brain doubted. Doubted that vision of heaven was real, maybe that heaven existed at all. And even if it did, doubted that her brother had made it there. She let herself slump and allowed her mind to rest inside the familiar blanket of Jamie’s chatter, ignoring her mother’s spirited small talk.

Her father shifted toward her. “The eulogy. It means a lot, to your mother.”

Alice nodded, and he reached a hand out, as if to lay it reassuringly on her shoulder, but pulled back at the last second and formed a fist at his side.

“He could never fight his demons,” her father said. “It’s better this way. For the family.”

She stepped back an inch, as if off-balance.

Before Alice could reply, the cheek of her nine-year-old daughter thumped onto her stomach. Her father looked at Caitlin, then turned away.

Alice reached down to stroke her daughter’s hair as her husband, Walker, strode through the crowd, standing six inches above even the tallest men, though they were all shrunken from age.

It’s better this way. For the family.

Could that really be true?

“She’s still pretty sensitive,” Walker said to Alice, with no explanation for his lateness or the dirty Converses on Caitlin’s feet that Maura was already eyeing. She tried to read his expression as Caitlin buried her head deeper into Alice’s dress. Though her daughter had never met her uncle, his dying had launched the concept of death into the air, as if she had only realized this week that it existed.

Two old men stood trapped between Richard’s handshake and Alice’s side hug in an awkward limbo. She gestured at Jamie, and he danced over to take Alice’s place in the line.

“You’re not going to die next, are you?”

“No, honey, I’m never going to die. You can’t get rid of me.”

Caitlin wiped her eyes with the back of her hand, leaving pink streaks down her cheeks. “Promise?”

“Well, we’ll die sometime,” Walker said, leaning down to her level. “When we’re old.”

“But you’re old now!”

Alice gave her husband a face that said Let me handle this, idiot but remembering what was to come, she mustered her last reserves of patience and morphed her expression into the same fake smile she’d used with the mourners. Better to hang onto what she expected would be their last hour of marital (somewhat) peace for weeks.

Alice leaned down to her daughter. “We won’t die for a very, very, very long time. Okay?”

Caitlin nodded, and the family stepped forward to greet the next mourner. The receiving line continued.

“How did he die?” one of the mourners asked Maura, the question petering out at the end. Alice raised an eyebrow and awaited the reply.

“Heart failure. So unexpected.”

Her mother always lied with a smile.

She would never tell the mourners the words that rattled in Alice’s skull now. Like the game of Pong her brother had been so happy to get for Christmas one year, the two words bounced in an endless loop: overdose, OxyContin, and back again. They were the only words Alice had retained after her mother delivered the news to her in the church parking lot on Sunday, saying simply, “Rob is dead. Heart failure.”

Then, to the only question Alice dared to ask: “His heart stopped beating when he overdosed on OxyContin. Is that what you want to hear?”

* * *

When, finally, the last mourner entered the church, Alice stepped away from Walker and her mother, now cheerfully introducing Caitlin to her Thursday bridge group. She walked past dozens of cross-shaped flower arrangements that threatened to collapse into

the crowd—all addressed to her mother—until she reached a table usually cluttered with church flyers.

Her mother had decorated it with a row of pictures that showed the two Tate children growing up. At various stages of childhood, they climbed their tree house, canoed on the river, hugged a golden retriever, or squeezed into the driver’s seat of one of their father’s eighteen-wheelers with Tate Trucking in block letters across the side. Alice’s cheeks burned with anger as she looked at their smiling faces. She longed to reach into the photo and pin him down there, to keep him from leaving, from dying.

Her eyes skipped over a photo of the young family in front of her parents’ house, a place she hadn’t been in years and hoped never to see again. She was sure her mother had brought the photo to torment her, as if her brother’s death and the tension with Walker were just shy of far enough.

The next photo showed the family’s annual trip to Amelia Island, the trip the year before her brother left. Five years younger, Alice was small enough to perch on his shoulders. Her legs dangled down over his strong arms, and she wore jean shorts and the T-shirt she’d received a few weeks earlier at her fourth-grade field day. She looked right into the camera, caught in mid-laugh. His neck and smile hid his other features as he tipped his face to look up at her.

She remembered thinking a day at the beach with her brother was the most fun she’d ever had, the most special she’d ever felt, his eyes focused on her as if he wore blinders to the rest of the world, while her father would barely look up from his newspaper when she talked, and her mother would only correct her grammar.

Was the family better off with him dead, as her father suggested? No. The only better reality would have been for him not to have existed at all, to erase these happy memories from her consciousness. Pretending her brother never existed, that’s how she’d chosen to live with Walker for the last decade, after all. The loss and loneliness of the years after her brother left were painful only because she had experienced the other reality, with him, the reality that had flooded back to her anew in each hour since his death.

How to Bury Your Brother

How to Bury Your Brother